To understand the Bhagavad Gita is to understand the necessity of action. While we often think of “duty” as an external obligation, the Gita argues that duty is an inevitable byproduct of existence itself.

The Core Meaning: Existence as Action

The Gita’s central philosophy can be distilled into a powerful analogy: To exist is to act.

Krishna explains to Arjuna that no one can remain inactive for even a moment. Even “doing nothing” is a choice—an action of the mind. Once you acknowledge “I exist,” you are already participating in the machinery of the universe (Prakriti).

- The Inevitability of Duty: Because you are part of the cosmic fabric, you have a function to perform, just as the sun must shine or the wind must blow. This is your Svadharma (inherent nature/duty).

- The Problem of Attachment: We suffer not because we act, but because we try to “own” the results of those actions.

- The Solution: If action is unavoidable, the only way to remain free is to act without self-interest. This is Nishkama Karma. You perform your duty simply because it is the “right” movement for a being in your position, not because you are chasing a specific reward.

The Connection: The Triple Foundation (Prasthanatrayi)

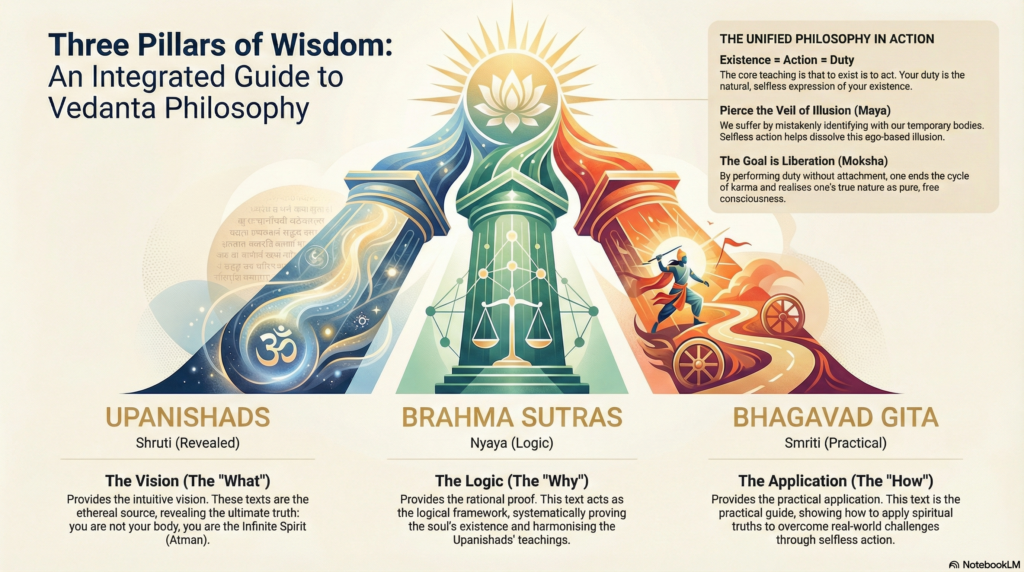

To see how the Gita fits into the larger puzzle of Indian philosophy, we must look at the Prasthanatrayi. These are the three canonical nodes of the Vedanta school.

| Text | Classification | Role |

| Upanishads | Shruti (Heard/Revealed) | The Intuitive foundation. They provide the “What” (The nature of Reality). |

| Brahma Sutras | Nyaya (Logic) | The Rational foundation. They provide the “Why” (The logical proof). |

| Bhagavad Gita | Smriti (Remembered) | The Practical foundation. They provide the “How” (The application in life). |

Defining The Brahma Sutras

While the Upanishads are poetic and the Gita is narrative, the Brahma Sutras (authored by Sage Vyasa) are purely analytical. They serve as the “connective tissue” that makes Hindu philosophy a rigorous science.

1. The Purpose: Reconciliation

The Upanishads were composed by different seers over centuries. To a casual reader, they might seem to contradict one another (e.g., some passages say God has a form, others say God is formless). The Brahma Sutras were written to systematize these teachings, proving they all point to one consistent truth.

2. The Format: Aphorisms (Sutras)

A “Sutra” is a thread—a very short, pithy statement designed to be memorized. For example, the very first Sutra is:

“Athato Brahma Jignasa” (Therefore, now, let us inquire into the Ultimate Reality.)

Because these statements are so brief, they are almost impossible to understand without a commentary (Bhashya). The greatest philosophers in history, such as Shankara and Ramanuja, wrote massive books just to explain these short lines.

3. The Content: Defining Brahman

The text methodically defines Brahman (The Absolute) as the source, the sustenance, and the end of the universe. It uses logic to refute rival schools of thought (like materialism or nihilism) and explains how the soul travels after death, the nature of liberation, and the relationship between the individual and the Infinite.

Brahma Sutras Regarding: The Soul and The Body

The Brahma Sutras use a rigorous logical framework called Nyaya to prove that the soul (Atman) is not merely a byproduct of the physical body. This is a crucial distinction because if the soul is just “matter,” then the Gita’s message of eternal duty becomes meaningless.

Here is the logical breakdown of how the Brahma Sutras prove the soul’s independence:

1. The Argument from Consciousness (Caitanyam)

The Sutras argue that matter (the body) is essentially unconscious and “object-like” (Drishya).

- The Logic: A collection of chemicals cannot produce a “knower.” Just as a camera can record an image but cannot “experience” the beauty of a sunset, the physical brain processes data, but the Atman is the witness that experiences it.

- The Conclusion: The “Subject” (the I) can never be the “Object” (the body).

2. The Argument from Purpose (Pararthatva)

The Sutras use the logic of “design.”

- The Logic: Any complex assembly—like a house or a chariot—exists for the sake of someone else (the resident or the passenger). The body is a complex assembly of organs and senses.

- The Conclusion: Therefore, the body must exist for the sake of a “User” who is not the body itself. That user is the Atman.

3. The “Unchanging” vs. The “Changing”

One of the most powerful proofs in the Sutras is the concept of Recognition.

- The Logic: Your body changes entirely over decades—every cell is replaced. Your thoughts and emotions change every second. Yet, you have a persistent sense of being the “same person” who existed ten years ago.

- The Conclusion: If everything about you was physical/mental, you would be a “new” person every moment. Since you remain “You,” there must be an underlying, unchanging substance: the Soul.

How this connects back to the Gita’s “Duty of Existence”

When you combine the logic of the Brahma Sutras with the ethics of the Gita, the picture becomes clear:

- The Sutras prove: You are an eternal, conscious Witness (Atman), distinct from your temporary body.

- The Gita explains: Because you are this eternal Witness currently “wearing” a body, you are automatically plugged into the world’s energy.

- The Result: You cannot claim to “exist” and “do nothing” simultaneously. By the very act of being alive, you are consuming breath, food, and space. Your duty is simply the movement of your particular soul-and-body complex back toward its source.

Key Takeaway: In this philosophy, “Doing your duty” isn’t a social contract; it is a metaphysical law. Just as a flame cannot exist without heat, a soul in the material world cannot exist without action.

Connection with the Upanishads

The relationship between the two is so close that the Gita is traditionally called “Gitopanishad” (The Upanishad of the Gita).

1. The Cow and Milk Analogy

The most famous traditional verse (from the Gita Mahatmya) explains their connection using a beautiful metaphor:

“All the Upanishads are the cows, the milker is Krishna, the calf is Arjuna, and the milk is the nectar of the Gita.”

In this view, the Upanishads are the vast, raw source of wisdom, and the Gita is the concentrated, digestible essence of that wisdom.

2. Practical vs. Theoretical

The Upanishads are often abstract and were historically taught in the quiet of a forest (the word Upanishad means “sitting down near” a teacher). They focus on the nature of the Atman (individual soul) and Brahman (universal reality). The Gita takes these same concepts—such as the immortality of the soul—and applies them to a battlefield, proving that spiritual wisdom isn’t just for monks, but for people facing real-world stress.

The Gita directly quotes or paraphrases many verses from the Upanishads, particularly the Katha Upanishad. For example:

- The Eternal Soul: Both texts emphasize that the soul is never born and never dies; it only “changes clothes” by moving from one body to another (2.22).

- The Chariot Metaphor: Both use the imagery of a chariot to represent the human condition, where the horses are the senses, the mind is the reins, and the Charioteer is the higher Intellect/God.

4. Part of the “Prasthanatrayi”

In Indian philosophy, to be considered an authoritative school of thought, one must comment on three specific texts called the Prasthanatrayi (The Three Foundations):

- The Upanishads (The revealed truth/Shruti).

- The Brahma Sutras (The logical foundation).

- The Bhagavad Gita (The practical application/Smriti).

The Gita serves as the bridge that connects the high-altitude philosophy of the Upanishads to the everyday actions of a human being.

Deep Connections

To dive deeper into the connection between these three, we have look again at how they form a single “nervous system” for Indian thought known as the Prasthanatrayi (The Triple Canon).

If the Upanishads are the inspiration, and the Brahma Sutras are the logic, the Gita is the actual lived experience.

1. The Relationship of Authority (Shruti vs. Smriti)

The connection starts with their “rank” in spiritual literature:

- The Upanishads (Shruti – “That which is heard”): These are considered the direct “revelation” of the universe. They are the highest authority. However, they are often cryptic, poetic, and scattered across different Vedic branches.

- The Bhagavad Gita (Smriti – “That which is remembered”): The Gita is technically “secondary” authority because it is part of an epic (The Mahabharata). However, it is called the “Milk” of the Upanishads. It takes the “Heard” truths and turns them into “Remembered” instructions for a person in crisis.

- The Brahma Sutras (Nyaya – “Logic/Method”): This text acts as the “Supreme Court” of the three. It uses pure reason to prove that the Upanishads and the Gita don’t contradict each other.

2. The Bridge: From “Being” to “Doing”

The deepest connection lies in how they handle your existence.

- Upanishadic Core: Focuses on Being. The famous “Great Sayings” (Mahavakyas) like Tat Tvam Asi (That Thou Art) tell you what you are (the eternal Atman).

- Gita’s Core: Focuses on Doing. It takes that “Being” and says: “Since you ARE the eternal Atman (as the Upanishads say), and since the Atman is part of the cosmic whole, you MUST act.” * The Brahma Sutras’ Core: Focuses on Reasoning. It explains why the Atman is eternal and how it is logically possible for an eternal being to reside in a temporary body.

- The Existential Link: The Brahma Sutras prove you are a “conscious agent” (Karta). The Gita then picks up that proof and says, “Since you are an agent, you cannot sit still. Your duty is the natural expression of your existence.”

3. Direct “Creative Remixes”

The connection is often literal. Lord Krishna frequently “remixes” verses from the Katha Upanishad to explain the nature of the soul to Arjuna.

| Concept | Katha Upanishad (1.2.18) | Bhagavad Gita (2.20) |

| The Soul | “The wise one is not born, nor dies… unborn, eternal, ancient.” | “It is not born, nor does it ever die… unborn, eternal, ever-existing.” |

| The Metaphor | Uses the Chariot to describe the Body/Mind/Soul hierarchy. | The entire Gita is spoken on a Chariot, turning the metaphor into a living reality. |

4. The Brahma Sutras as the “Systematizer”

The Brahma Sutras are vital because the Upanishads can be confusing. One Upanishad might say “All is One,” while another implies a “God” separate from the “Soul.”

The Brahma Sutras reconcile this by categorizing the teachings:

- Samanvaya (Harmony): Proves all Upanishads point to the same Brahman.

- Avirodha (Non-conflict): Refutes logical objections (like the ones Arjuna raises about why he should have to fight).

- Sadhana (Practice): Details the methods of meditation—which the Gita then expands into the four Yogas.

- Phala (Fruit): Describes the state of liberation—which the Gita calls “becoming Brahman” (Brahmabhuta).

Analogy: The Flow of Wisdom

If you think of spiritual knowledge as water:

- The Upanishads are the clouds (The high, ethereal source).

- The Brahma Sutras are the plumbing (The logical structure that directs the water).

- The Bhagavad Gita is the glass of water (The practical portion you can actually drink to quench your thirst).

Summary: The Integrated Circuit

- Upanishads: Provide the Vision (The Soul exists).

- Brahma Sutras: Provide the Proof (The Soul must exist for these logical reasons).

- Bhagavad Gita: Provides the Requirement (Because the Soul exists, you have a duty to act).

Leave a Reply